What makes a good Integrated Development Environment (IDE)?

Well, it depends on a specific developer, language, workspace and its restrictions so on.. In short, there is no one answer to the above question. However, there are few salient features that is objectively constant, something that all developers appreciate, A bare minimum if you will.

Here are the common features that make an IDE good IMO

- Spell checker

- Syntax highlighting

- Linter

- Support Language server

- Compilation

- Debugger

Throughout this blog, I will try to describe the above features and how to get a reasonable working setup with Emacs for each of this features.

C/C++ code. My setup is aimed at working with aforementioned languages. But with few tweaks, it can be ported to any language. My goal here is to provide enough resources to get startedSpell checker#

flyspell. It is a client of sorts that runs gnu aspell

application under-the-hood to provide spelling suggestions. The configuration might look something like below

;; Spell check. Requires 'aspell' under-the-hood

(use-package flyspell

:ensure nil ;;Inbuilt package

:hook (text-mode . flyspell-mode)

:config

(flyspell-mode 1))

I enable flyspell using use-package and hook it into all the text-mode files (org files, program source files, etc…). In the end I enable flyspell-mode to be globally enabled

The way it works is,

- When there is a spelling mistake, the Editor underlines it with red squiggly line

- You press Meta + $ on the squiggly lines to pull-up the recommendations for the misspelled word

- You press the keys associated with each suggested word and it replaces the misspelled word.

Here’s how it looks

Syntax highlighting#

Syntax highlighting refers to coloring text that uniquely represents a type/class.

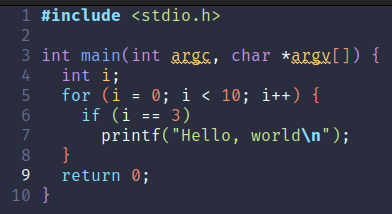

For reference, notice how the data types like char, int are in purple, the language keywords like for, if, return are in teal and so-on.

Historically, this was done with the help of language parsers. Each language would have a syntax parser that would break the code into a know regexp pattern and serve to the the IDE to then be highlighted. Although good, there are some notable issues with this approach and it is very rigid.

A more recent approach exists known as tree-sitter . It incrementally builds the language nuances into a syntax tree and is very robust IMO.

To use it with Emacs, we need to enable a tree-sitter mode. This is typically a well known major mode with -ts- in its name. For example,

| Legacy mode | Treesit equivalent | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| c-mode | c-ts-mode | Major mode for editing ‘C’ source files |

| c++-mode | c++-ts-mode | Major mode for editing ‘C++’ source files |

The configuration looks something like this

;; Regexp magic. Auto mode for *.c and *.h files

(use-package c-ts-mode

:ensure nil ;;inbuilt package

:mode("\\.[ch]\\'" . c-ts-mode))

;; Regexp magic. Auto mode for *.cpp and *.hpp2 files

(use-package c++-ts-mode

:ensure nil ;;inbuilt package

:mode("\\.[ch]pp\\'" . c++-ts-mode))

Installing language grammar#

After the above configuration, when you try to load a c/cpp source file. You would be presented by a message that might look like this

⛔ Warning (treesit): Cannot activate tree-sitter, because language grammar for cpp is unavailable (not-found): .config/emacs/tree-sitter/libtree-sitter-cpp: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory /.config/emacs/tree-sitter/libtree-sitter-cpp.0: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory /.config/emacs/tree-sitter/libtree-sitter-cpp.0.0: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory /.config/emacs/tree-sitter/libtree-sitter-cpp.so: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory /.config/emacs/tree-sitter/libtree-sitter-cpp.so.0: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory /.config/emacs/tree-sitter/libtree-sitter-cpp.so.0.0: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory libtree-sitter-cpp: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory libtree-sitter-cpp.0: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory libtree-sitter-cpp.0.0: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory libtree-sitter-cpp.so: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory libtree-sitter-cpp.so.0: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory libtree-sitter-cpp.so.0.0: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

This basically means

Although you have enabled the “ts” mode, you have not installed the appropriate language grammar for this type of file

To fix this, M-x treesit-install-language-grammar and follow the installation. To ease in the installation, you can pre-configure the language-grammar source paths and their compatible versions as shown below.

(use-package treesit

:ensure nil ;;Inbuilt package

:config

(setq treesit-language-source-alist

'((c . ("https://github.com/tree-sitter/tree-sitter-c" "v0.24.1"))

(cpp . ("https://github.com/tree-sitter/tree-sitter-cpp" "v0.23.4")))))

Linter#

Take a look at the code below

int x = 5; // ✅ valid syntax

int x 5 = ; // ❌ invalid syntax

Intuitively, we know that the first statement is the correct syntax and the second statement is incorrect. The IDE does this with the help of a syntax-checker. Emacs ships with flymake syntax checker by default. There is another popular alternative called flycheck. Here’s the installation

;; On the fly syntax and linting check for all text mode. Faster than flymake + Better functionality

(use-package flycheck

:ensure t

:hook (prog-mode . flycheck-mode))

We install flycheck and hook it into all the prog-mode (which is a major parent mode for all programming languages)

Language server#

Traditionally, IDEs used to ship with a dedicated build utilities. However, with ever-evolving programming languages, their standards and new programming languages added in, it does not make sense to add new IDEs for every programming language out there!

To abstract IDEs from build infra, Microsoft created Language Server Protocol (LSP) . It is a standard that most of the new IDEs comply to. The way this works is,

- There is a language server based on the language you are editing running in the background

- Every movement, edit etc are sent to these servers over LSP and the IDE receives back a response on how to interpret the user-action

- The IDE in-turn notifies the user (variable does not exist, No such file found, did you mean this? etc…)

Emacs conveniently abstracts the language server interaction such that the way you interact with every language server (c, cpp, python etc..) is the same. Emacs provides a LSP client called Eglot that ships with newer Emacs by default. We summon this client as below

(defun custom/elgot-post-attach-hook ()

(eglot-inlay-hints-mode -1)

(local-set-key (kbd "C-c l") 'eglot-prefix-map)

(define-key eglot-prefix-map (kbd "fb") #'eglot-format-buffer)

(define-key eglot-prefix-map (kbd "fr") #'eglot-format)

(define-key eglot-prefix-map (kbd "r") #'eglot-rename)

(define-key eglot-prefix-map (kbd "q") #'eglot-code-action-quickfix))

(use-package eglot

:ensure nil ;;Internal package

:hook ((eglot-managed-mode . custom/elgot-post-attach-hook))

:config

(define-prefix-command 'eglot-prefix-map)

(add-to-list 'eglot-server-programs

'((c-ts-mode c++-ts-mode) . ("/usr/bin/clangd"))))

We configure the Eglot by sharing it the mode vs program configuration. This tells eglot what to run when enabled in a specific mode. But, this does not auto launch!

Also, there are bunch of keyboard shortcuts that ease up frequently used commands.

To auto launch an eglot instance, we need to update the configuration for each supported program mode. This way, when one of the below major-mode is activated, the buffer would be managed by Eglot. I.e Eglot manages and communicates the changes to-and-from a LSP server. How cool is that!!

(use-package c-ts-mode

:mode("\\.[ch]\\'" . c-ts-mode)

:hook ((c-ts-mode . eglot-ensure)))

(use-package c++-ts-mode

:mode("\\.[ch]pp\\'" . c++-ts-mode)

:hook ((c++-ts-mode . eglot-ensure)))

Additionally, to begin unleashing complete potential of elgot, you need a compilation database which is essentially a compile_commands.json file that records all the project dependencies and presents it to Eglot. To generate such a database based on your build system (CMAKE, make, waf…) checkout here

Compilation#

Any good language needs compilation 😉 (python folks assemble!)

If your project is version controlled using for example git, then you are in luck. Emacs ships with a package called project.el that does all things project-management.

Ctrl-x + p is your entry-point for all things project-management. Notice that Ctrl-x + pc will run project-compile at the root of the project. This is very handy for multiple compilations (both repetitive and debug/release builds).

The variable compile-command dictates the compilation command to run when project-compile is evaluated. You can either configure it in your configuration init.el file or a better approach is to have a .dir-locals-el file per-project at project’s root and add the below line.

((nil .

((compile-command . "./build.sh"))))

This runs build.sh on every compilation. You can script your own build commands to build your project. Here is an example for one of my projects

# !/bin/bash

if [ ! -d build ]; then

mkdir build

fi

cmake -S . -B build

make -C build

The directory looks like this

Debugging#

Emacs ships with gdb and gud-gdb. I prefer the latter. Currently, I use it as-is without any configuration and seems to be working quite well for me. For the curious and tinkers among you gnu documentation on emacs gdb

is a great starting point

Its worth mentioning dape.el and dap-mode . Both of which leverage the modern Debug adapter protocol to have debug equivalent of LSP

Conclusion#

My development needs are ever-evolving. I have just started to scratch the surface of what is possible. At the moment, the setups/configs mentioned above seems to get the job done. I always keep tinkering with my setup and this might evolve in the near future.

As always, it was a blast to be able to configure and summon the beast 😁